Quantitative Easing Explained: Main Talking Points

- With interest rates near zero, the Federal Reserve ventured another policy tool in quantitative easing

- After years of QE, the Bank of Japan has experienced diminishing economic and financial returns

- Similarly, the ECB has engaged in long-term refinancing operations (LTROs) as a form of quantitative easing, but their effectiveness remains in question

How Does Quantitative Easing Work?

Quantitative easing (referred to as ‘QE’) is a monetary policy tool typically used by central banks to stimulate their domestic economy when more traditional methods are spent. The central bank buys securities – most frequently government bonds – from its member banks, effectively increasing the supply of money in the economy.

With increased supply, the cost of money is reduced which makes it cheaper for businesses to borrow money to use for expansion. This has a similar effect to the standard interest short-term interest rate cuts that central banks employ; but depending on what they purchase, such efforts can lower the cost for significantly longer loans. That could more directly influence lending for homes, autos and small businesses.

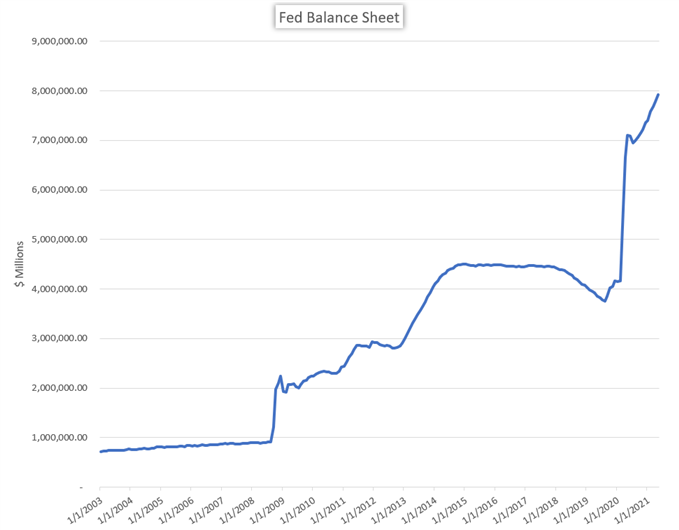

The Federal Reserve Bank (FED) Quantitative Easing Policy

As the central bank of the United States, the Federal Reserve has a duty to provide the nation with a safer, flexible and more stable monetary and financial system. That is often boiled down into a stated dual mandate of steady inflation and low unemployment. In pursuit of these objectives, the Fed is allotted a series of monetary policy tools that allow it to influence the US Dollar and the money supply in the country. While raising and lowering the Federal Funds rate is the most widely known tool, the central bank’s balance sheet has become one of heightened importance and investor interest.

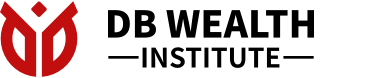

Federal Reserve Bank Total Assets

Simply put, the Fed’s balance sheet is the same as any other balance sheet. In the Fed’s case, it records the collection of distinct assets and liabilities across all the Federal Reserve bank branches. The bank can use these assets and liabilities as an unconventional or supplementary monetary policy tool, particularly when interest rates are already low and confer limited potential with further policy efforts.

In 2008, as the United States economy entered a recession amid the Great Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve announced a series of interest rate cuts. As a typical expansionary tool, the cuts were intended to spur spending thereby improving the economy. However, even with interest rates near zero, economic recovery failed to take hold.

Then, in November 2008, the Federal Reserve announced its initial round of Quantitative Easing, popularly known as QE1. The announcement saw the Fed massively shift its standard market operations as it began to purchase significant amounts of treasury bills, notes and bonds, along with asset- and mortgage-backed securities of high quality. The purchases effectively increased the supply of money in the US economy and made access to capital less expensive. The buying program lasted from December 2008 to March 2010 and was accompanied by another cut to the Fed Funds rate, resulting in a new range of 0 to 0.25% interest.

Change in Fed Balance Sheet due to Quantitative Easing

With the Federal Funds rate near 0, and not willing to explore negative rates at the time, the central bank had effectively expended all its expansionary monetary policy tools. Thus, quantitative easing became an important part of the central bank’s toolbox to boost economic growth and right the capsized ship that was the US economy.

To further aid recovery, the Fed pursued subsequent rounds of Quantitative Easing, now known as QE2 from November 2010 to June 2011 and QE3 from September 2012 to December 2013. The purchase programs targeted similar assets and helped to prop up perceived growth – as well as capital markets as a side effect – in the US until the central bank finally reversed course by raising its benchmark rate for the first time in December 2015.

View our free Quarterly Forecasts for the US Dollar, Euro , Dow Jones and more.

Having already started to reduce its balance sheet in 2018, we have seen debate over a sustained Quantitative Tightening (reducing the balance sheet) pop up in 2019. Many Federal Reserve officials have supported the slow drawdown of the bank’s balance sheet and advocated for further normalization as the US economy boasts over a decade of economic expansion. However, uneven growth and external risks like trade wars have complicated the issue of this exceptional support.

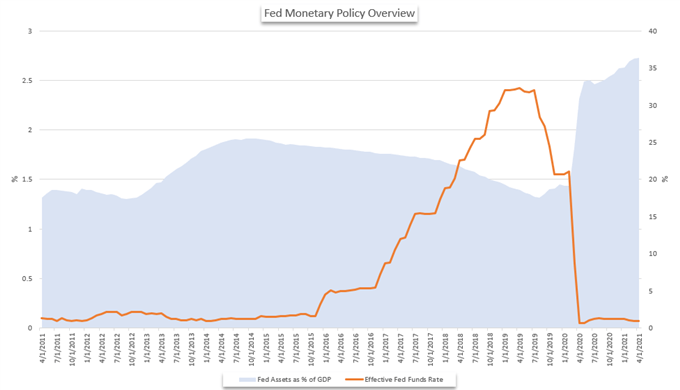

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) Quantitative Easing Policy

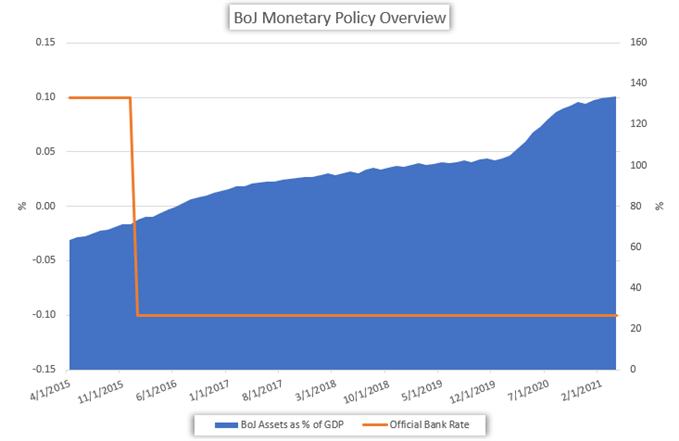

Japan’s central bank is another financial institution that has employed the use of quantitative easing, but with varying degrees of success. One of the first instances occurred between October 1997 and October 1998 when the BOJ purchased trillions in Yen of commercial paper in an attempt to help banks through a period of low growth, low interest rates and trouble from bad bank loans. However, growth remained subdued.

View our Economic Calendar for data releases and live event times.

In light of the underwhelming impact, the Bank of Japan increased asset purchases between March 2001 and December 2004. This round of purchases targeted long-term government bonds and injected 35.5 trillion Yen in liquidity to Japanese banks. While the purchases were moderately effective, the purchase of long-term government bonds suppressed asset yields and at the advent of the Great Financial Crisis , Japan’s growth vanished once again. Since then, the Bank of Japan has conducted numerous rounds of QE and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) all of which were largely ineffective as the country struggles with low economic growth despite a negative interest rate environment.

Today, the Bank of Japan has branched out to other forms of asset purchases with varying degrees of quality. Alongside previous purchases of commercial paper, the bank has built up considerable ownership of the country’s exchange traded fund (ETF) market and Japanese real estate investment trusts or J-REITs.

The BOJ began ETF purchases in 2010 and as of 2Q 2018 owned roughly 70% of the total Japanese ETF market. Further, these broad purchases have made the central bank a majority shareholder in over 40% of all public Japanese corporations according to Bloomberg. Thus, the quality and credit rating of these holdings by the central bank are fundamentally weaker than that of a government issued assets like Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) and differ considerably from holdings of the Federal Reserve.

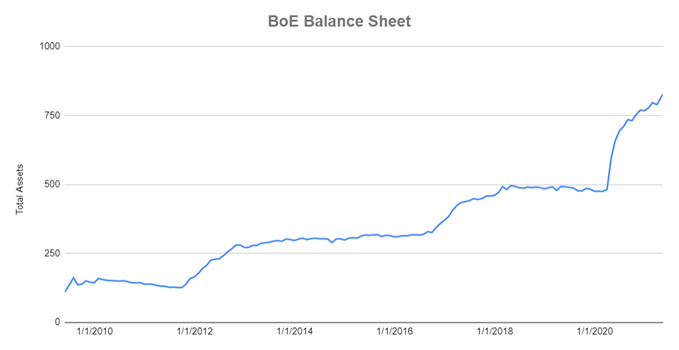

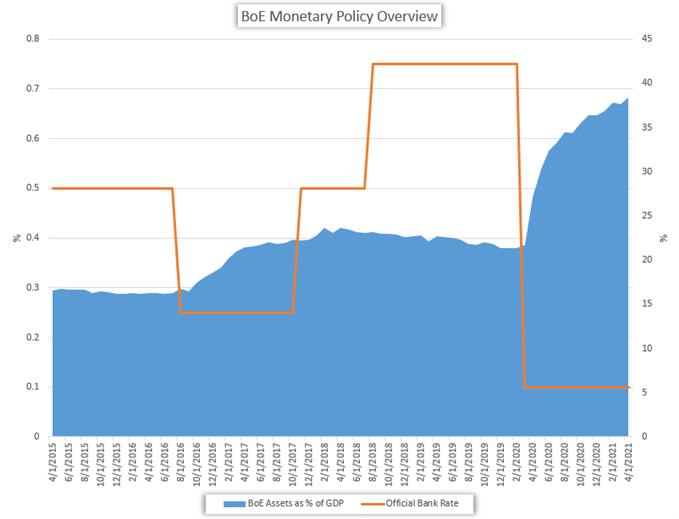

The Bank of England (BOE) Quantitative Easing Policy

Like the previously mentioned central banks, the BOE has amassed large sums of local government bonds (GILTs) and corporate bonds through its own quantitative easing. The policy was pursued to bolster the UK’s economy during the height of the global recession which would eventually carry over to the added risk of political risks from a Scottish Referendum vote, General Election and eventually the Brexit. At the same time, the bank has increased its overnight lending rate slowly.

In contrast to its American and Japanese counterparts, the overall holdings of the UK’s central bank are significantly smaller. When compared to national GDP, the Bank of England’s holdings amount to a mere 5.7% in early 2019, paling in comparison to Japan’s holdings that equate to more than 100% of GDP. The relatively small holdings may allow the bank to act more effectively in the future as the diminishing returns of QE have yet to take hold.

At present, the efficacy of the BOE’s quantitative easing strategy appears to top that of the BOJ and fall inline with that of the Federal Reserve. As the uncertainties of Brexit persist, the bank may decide to maintain its safety net or perhaps even further its monetary policy measures. That being said, the bank would remain far less committed to quantitative easing than its neighbor, the European Central Bank.

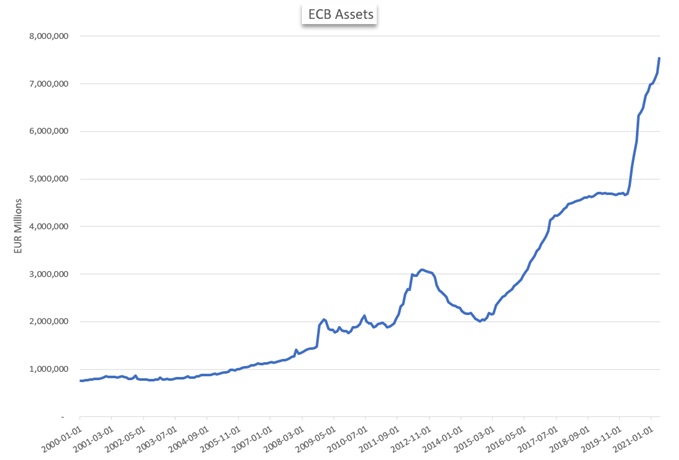

The European Central Bank (ECB) Quantitative Easing Policy

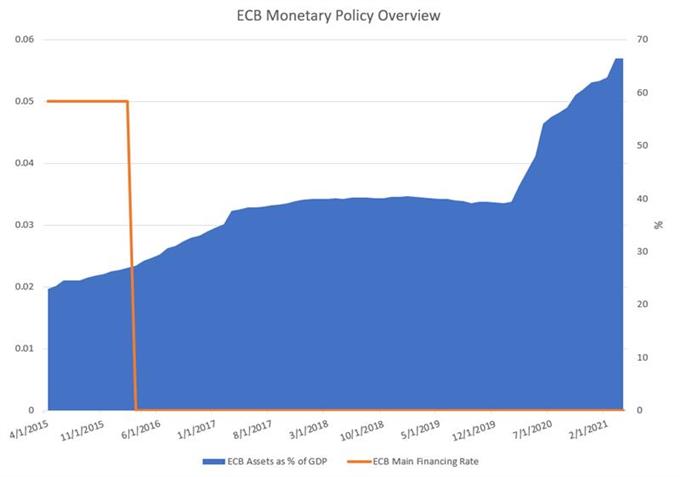

The ECB is another major central bank that has pursued quantitative easing as an expansionary tool – though its foray into the now conventional QE came significantly latter than the Fed’s. In its most recent round of easing, the European Central Bank spent nearly $3 trillion buying government bonds and corporate debt, along with asset-backed securities and covered bonds.

The purchases were conducted from March 2015 to December 2018 in an effort to avoid sub-zero inflation from plaguing the European bloc which was still in recovery from the dual scourge of the global recession and then the Eurozone Debt Crisis. According to Reuters, the purchases came at a pace of 1.3 million Euros a minute, equating to 7,600 Euros per person in the bloc.

Like Japan, the ECB’s easing rounds proved rather ineffective. In early 2019, the bank announced another round of easing through targeted long-term refinancing operations or TLTROs, just months after the end of its opened-ended QE program and as interest rates remain at 0. TLTROs provide an injection of low interest rate funding to banks in the Eurozone in an effort to provide greater bank liquidity and lower sovereign debt yields. The loans carry a maturity of one to four years.

TLTROs aim to stabilize the balance sheet of private banks and their liquidity ratio. A stronger liquidity ratio allows the bank to lend more readily which in-turn, pushes down interest rates and should allow for inflation. However, years of monetary stimulus can see diminishing returns and have negative implications.

Negative Effects of QE: Balance Sheet Use and Diminishing Returns

While QE proved fruitful for the Federal Reserve and the United States, the monetary policy tool has proved less effective for the central banks of Japan and Europe and has even contributed some negative consequences. For the Japanese economy, years of expansionary policy has resulted in deflation and the bank’s balance sheet now carries more value than the GDP of the country.

Further, its large share of ownership of the ETF, JRIET and government bond market may put it at heightened risk in the eventuality of an economic downturn. Despite numerous rounds of stimulus and negative interest rates, economic growth has failed to take hold and the Japanese central bank is wading into unknown monetary policy territory.

Similarly, the ECB has seen its own form of quantitative easing exert less influence over the European economy as inflation and growth remain muted in the bloc.

The Impact of Quantitative Easing on Currencies

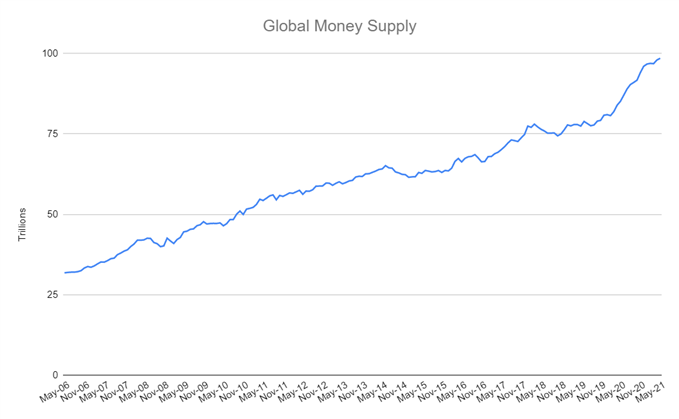

Fundamentally, the use of quantitative easing increases the supply of a currency. According to the commanding principles of supply and demand, such a change should result in the price of that currency decreasing. However, as currencies are traded in pairs, the resulting weakness in one currency is relative to its counterpart.

With the current monetary policy climate trending toward flush supply and dovish tones, few currencies herald absolute strength. That said, strength has recently been garnered through an almost best-of-the-rest mentality in which a dovish shift from one central bank is followed shortly thereafter with dovishness from another bank. Such subtle competitive policies can turn more aggressive, resulting in what is termed a ‘currency war’.

Consequently, the global supply of money has ballooned while the relative value of currencies remains in flux. In the current monetary policy climate, differences in approach have largely become a comparison in dovishness. Among the major central banks, few stand on the hawkish side of policy and fewer still have plans to raise their central interest rate. Instead, officials have resorted to rounds of capital injection as quantitative easing appears to be gaining popularity as a monetary policy tool – though whether it remains as a permanent one remains to be seen.

Further reading on central banks and monetary policy

- Learn more about how central banks impact forex

- View the central banks calendar to track upcoming meetings

--Written by Peter Hanks, Strategist for .com